Lazy Pull, Smart Scale, eBPF Network

Stargz Snapshotter, Karpenter vs Cluster Autoscaler, and Cilium kube-proxy replacement

Welcome back to Podo Stack. This week: how infrastructure deals with scale. Three layers of optimization — images, nodes, network. Each one solves a problem you’ve probably hit.

Here’s what’s good this week.

🏗️ The Pattern: Lazy Image Pulling with Stargz

The problem

You’re scaling up. 50 new pods need to start. Every node pulls the same 2GB image. At the same time. Your registry groans. Your NAT gateway bill spikes. Containers sit there waiting instead of running.

Here’s the kicker: research shows your app uses about 6% of the files in that image at startup. The other 94%? Downloaded “just in case.”

The solution

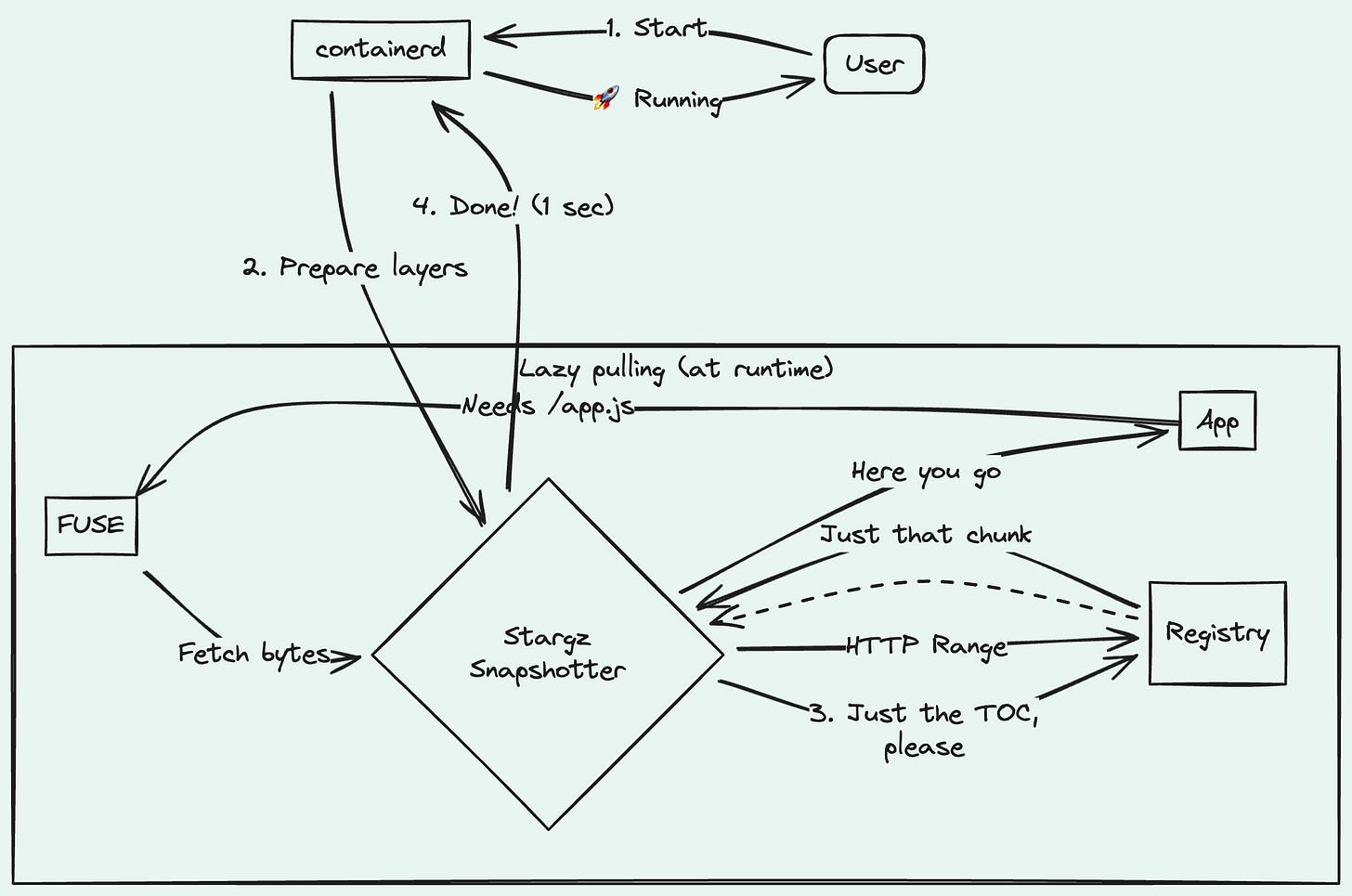

Stargz Snapshotter flips the model. Instead of “download everything, then run” — it’s “run now, download what you need.”

The trick is a format called eStargz (extended seekable tar.gz). Normal tar.gz archives are sequential — to read a file at the end, you unpack the whole thing. eStargz adds a TOC (Table of Contents) at the start. Now you can jump directly to any file.

When your container starts:

Snapshotter fetches the TOC (kilobytes, not gigabytes)

Mounts the image via FUSE

Container starts immediately

Files get fetched on-demand via HTTP Range requests

The container is running while the image is still “downloading.” Wild, right?

How this connects to Spegel

In Issue #1, we covered Spegel — P2P caching that shares images across nodes. Stargz takes a different approach: instead of optimizing *distribution*, it optimizes *what gets downloaded* in the first place.

They’re complementary. Spegel says “pull once, share everywhere.” Stargz says “only pull what you need.” Use both and your image pull times will thank you.

The catch

FUSE runs in userspace, so there’s some overhead for I/O-heavy workloads. Databases probably shouldn’t use this. But for your typical microservice that loads a few MB at startup? Perfect fit.

Links

⚔️ The Showdown: Karpenter vs Cluster Autoscaler

Two autoscalers. Same job. Very different approaches.

Cluster Autoscaler (the veteran)

CA has been around forever. It works through Node Groups (ASGs in AWS, MIGs in GCP). When pods are pending:

CA checks which Node Group could fit them

Bumps the desired count on that ASG

Cloud provider spins up a new node from the template

Node joins cluster, scheduler places pods

Time from pending to running: minutes. And you’re stuck with whatever instance types you pre-defined in your node groups.

Karpenter (the new approach)

Karpenter skips node groups entirely. When pods are pending:

Karpenter reads their requirements — CPU, memory, affinity, tolerations

Calls the cloud API directly (EC2 Fleet in AWS)

Provisions a node that exactly fits what’s waiting

Node joins, pods run

Time from pending to running: seconds. And it picks the cheapest instance type that works.

The comparison

Cluster Autoscaler:

Model: Node Groups (ASG)

Speed: Minutes

Sizing: Fixed templates

Cost: Often over-provisioned

Consolidation: Basic

Karpenter:

Model: Group-less

Speed: Seconds

Sizing: Right-sized

Cost: Optimized

Consolidation: Active

Karpenter also does active consolidation. It constantly checks: “Can I replace these three half-empty nodes with one smaller node?” If yes, it does.

The verdict

New cluster? Go Karpenter.

Already running CA successfully? Maybe keep it. Migration has costs. If it’s not broken, weigh carefully.

Links

🔬 The eBPF Trace: Cilium Replaces kube-proxy

The problem

kube-proxy uses iptables. Every service creates rules. Every rule gets checked sequentially.

1000 services = thousands of iptables rules. Every packet walks the chain. O(n) lookup. In 2025. In your kernel.

At scale, this hurts. CPU spikes during rule updates. Latency creeps up. Source IPs get lost in the NAT maze.

The fix

Cilium replaces all of this with eBPF. Instead of iptables chains, it uses hash map lookups — O(1), regardless of how many services you have.

helm install cilium cilium/cilium --set kubeProxyReplacement=trueOne flag. That’s it.

eBPF programs intercept packets before they hit the iptables stack, do a single hash lookup, and route directly. Faster, simpler, and source IPs stay intact.

Real numbers

I’ve seen clusters go from 2-3ms service latency to sub-millisecond after switching. CPU usage during endpoint updates dropped significantly. The larger your cluster, the bigger the difference.

Links

🔥 The Hot Take: eBPF is Eating Kubernetes

Look around. The data plane is being rewritten:

kube-proxy → Cilium eBPF

Service mesh sidecars → Cilium, Istio Ambient (ztunnel)

Observability → Pixie, Tetragon

Security → Falco, Tracee

The pattern is clear. Userspace proxies are getting replaced by kernel-level programs.

My hot take: In 3 years, half of the Kubernetes data plane will run on eBPF. The kernel is the new platform.

Agree? Disagree? Reply and tell me I’m wrong.

🛠️ The One-Liner: Karpenter Drift Detection

kubectl get nodeclaims -o custom-columns='NAME:.metadata.name,DRIFT:.status.conditions[?(@.type=="Drifted")].status'Karpenter tracks “drift” — when a node no longer matches its NodePool spec. Maybe the AMI updated. Maybe requirements changed.

This command shows which nodes are marked as drifted and will be replaced during the next consolidation cycle.

Pairs nicely with the Showdown section above. Once you’re on Karpenter, this becomes part of your daily toolkit.

If you’re not on Karpenter yet

kubectl top nodes --sort-by=cpu | head -5Shows your most loaded nodes. Useful for spotting where scaling is needed.

Questions? Feedback? Reply to this email. I read every one.

🍇 Podo Stack — Ripe for Prod.

Solid breakdown! The Karpenter seconds-vs-minutes comparison really nails why it matters in production. One thing I'd add: the ASG model also creates noisy neighbor problems when you batch workloads with different profiles into the same node group. Karpenter's bin-packing per pod spec basically eliminates that. Migration friction is real tho, especially if teams rely on ASG lifecycle hooks or specific launch tempaltes.